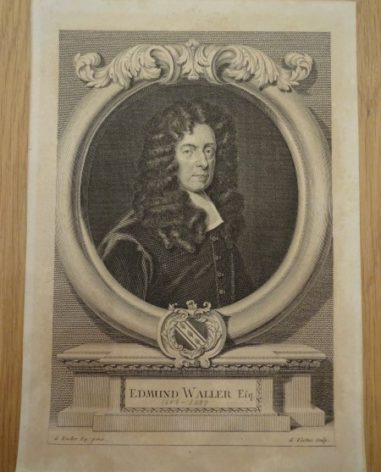

Edmund Waller

(1606-1687)

At Eton : c.1618-1621

Writers, Poets, Wits, Scholars and Dons

Known for: As a poet, Waller was known mainly for his panegyrics, which seem also to have served his agenda of political pragmatism and agility.

School Days: One of the few poets to have led a life of wealth and comfort, Edmund Waller was born to Robert and Anne Hampden, at his father’s estate in Buckinghamshire in 1606, three years into the reign of James I.

He was at Eton around 1618-1621[1] and before going up to Cambridge where, in common with wealthy young men of the time, he did not take a degree. He was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1622.[2]

Life and career: Waller was a courtier at the court of Charles I, and served as an MP in the turbulent decades of the personal rule and the early part of the civil war. He remained in parliament after the outbreak of civil war, with the king’s approval. In 1643 it appears that he and other moderates devised a plot which would facilitate the entry of Royalist forces into London. The plot was discovered and denounced to parliament by the Puritan John Pym. The apparent threat of violence undermined the moderates’ efforts to secure peace between king and parliament, with the continuation of war now inevitable.

Charitable accounts of Waller’s political career emphasise his pragmatism and efforts to persuade Parliamentarians and Royalists to pursue a path of compromise. In 1641, for instance, he made a speech in Parliament in support of the episcopacy, on the basis that it formed a bulwark against a potential social revolution in which he feared ‘ we may, in the next place, have as hard a taske to defend our propriety, as we have lately had to recover it from the prerogative.’[3] Such an argument appealed to the self-interest of some Parliamentarians, as well as to those who were genuinely concerned that the social fabric of the country would be rent asunder. It offered little appeal, however, to those at the more extreme end of the reforming political spectrum. More brutal assessments of Waller portray him either as an abject coward (Clarendon), or as a scheming trimmer who managed to survive the discovery of his plot, and returned to favour after the Restoration. Even the Eton Register records that their alumnus ‘informed against his fellow plotters to save his life.’ [4]

Whichever unflattering assessment one prefers, Waller was certainly an accomplished orator. Even the scathing Clarendon was forced to admire the Ciceronian powers he displayed at his trial:

‘A man … very powerful in language, and who, by what he spoke and the manner of speaking it, exceedingly captivated the good-will and benevolence of his hearer; which is the highest part of an orator; so that, in truth, he does as much owe the keeping his head to that oration, as Catiline did the loss of his to those of Tully.’[5]

He was imprisoned in the Tower of London in and, at the end of 1644, was allowed to go into exile. He clearly managed his relationships with his captors well, as he married his second wife during his confinement, and they went on to produce 13 children together.

As a poet, Waller was known mainly for his panegyrics, which seem also (whatever their literary merits) to have served his agenda of political pragmatism and agility. Among his collected works are found a series of poems, which testify to his political contortions:

‘Of His Majesty’s Receiving the News of the Duke of Buckingham’s Death.’

George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, was the singularly unpopular favourite of James I and, subsequently, of his son Charles I. Undaunted by this the first stanza of this poem draws irony-free parallels between Buckingham and Patroclus, the beloved companion of Achilles:

‘Nor was the stream of thy devotion stop’d

When from the body such a limb was lop’d.

As to thy present state was no less maim;

Tho’ thy wise choice has since repair’s the same,

And Homer durst not so great virtue feign

In his best pattern: of Patroclus slain.’

Charles is compared favourably both to Achilles and, subsequently, to King David whom he is said to surpass in fortitude and self-control. The Stuart monarch is portrayed displaying a different and, in Waller’s account, a superior form of heroism to that of mere military might.

It comes, then, as something of a surprise to find the following in this same poet’s oeuvre:

‘A Panegyric to My Lord Protector, of the Present Greatness and Joint Interest of His Highness and This Nation.’ (1654)

Having been exiled in 1644 for his part in the plot mentioned above, Waller was pardoned and permitted to return in 1552. The poet was a distant kinsman of Cromwell, through marriage, and a cousin of John Hampden, so it is perhaps not entirely surprising that he sought help fro these quarters, despite his earlier alignment with the royalist cause. In this poem he positions the Protector as bringer of peace, and defender of the nation:

‘Your drooping country, torn with civil hate,

Restored by you is made a glorious state;

The seat of empire, where the Irish come,

And the unwilling Scotch to fetch their doom.’

It appears, also, that he has found another David:

‘…

Born to command, your princely virtues slept,

Like humble David’s, while the flock he kept.

But when your troubled country called you forth,

Your flaming courage, and your matchless worth,

Dazzling the eyes of all that did pretend,

To fierce contention gave a prosperous end,

‘To the King upon His Majesty’s Happy Return’

Given the above, it is not difficult to imagine the difficulties in which the 1660 restoration of Charles II now placed Waller. To the modern ear, the tone of this next poem is almost risible, but such obsequiousness was by no means unusual. The poet, with what can only be described as chutzpah, once more reverses his political position, and has the temerity not only to adopt the position of miserable supplicant himself, but to extend this abasement to his fellow countrymen.

That, if Your Grace incline that we should live,

You must not (SIR) too hastily forgive.

Our guilt preserves us from th’ excess of joy,

Which scatters spirits, and would life destroy.All are obnoxious, and this faulty Land

Like fainting Hester doth before you stand,

Watching Your Scepter, the revolted Sea

Trembles to think she did Your Foes obey.… … … …

Faith, Law and Piety, that banisht train;

Justice and Truth, with You return again:

The Cities Trade, and Countries easie life

Once more shall flourish without fraud or strife.

Your Reign no less assures the Ploughmans peace,

Than the warm Sun advances his increase:

And does the Shepheards as securely keep

From all their fears, as they preserve their sheep.But above all, the Muse-inspired train

Triumph, and raise their drooping heads again;

Kind Heav’n at once has in Your Person sent

Their sacred Judge, their Guard, and Argument.’

Given the above, it is tempting to identify Waller’s greatest achievement as dying in his own bed at the age of 81 and, in dangerous times, survival is surely a skill. In addition to this, however, he was a much-admired poet, who did not altogether confine himself to self-serving panegyrics, and numbered Dryden among his contemporary admirers.

By Marie Harrison, Museum Custodian

References:

[1] Eton Register https://archives.etoncollege.com/Filename.ashx?tableName=ta_registers&columnName=filename&recordId=1 accessed 25th Oct. 2020

[2] Chernaik, Warren, ‘Edmund Waller’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/28556 ;

[3] Waller, E., 1606-1687. (1641). A speech made by master waller esquire, in the honourable house of commons, concerning episcopacie, whether it should be committed or rejected London, s.n.]. Retrieved from https://ezproxy-prd.bodleian.ox.ac.uk:2082/docview/2240884147?accountid=13042 ; accessed 8/11/2020

[4] Eton Register (as above)

[5] Clarendon, The History of the Rebellion and the Civil Wars in England, 3.52; cited in Chernaik op.cit.